*This piece follows our earlier instalment, The Hidden Legacy of USAID, which uncovered how “aid” has been used to dominate food systems across the Majority World. In this instalment, we turn to Africa, where the rejection of dependency has long been met with violence. Because behind every revolution cut short was a vision the empire feared: sovereign, self-determined, and rooted in the soil.

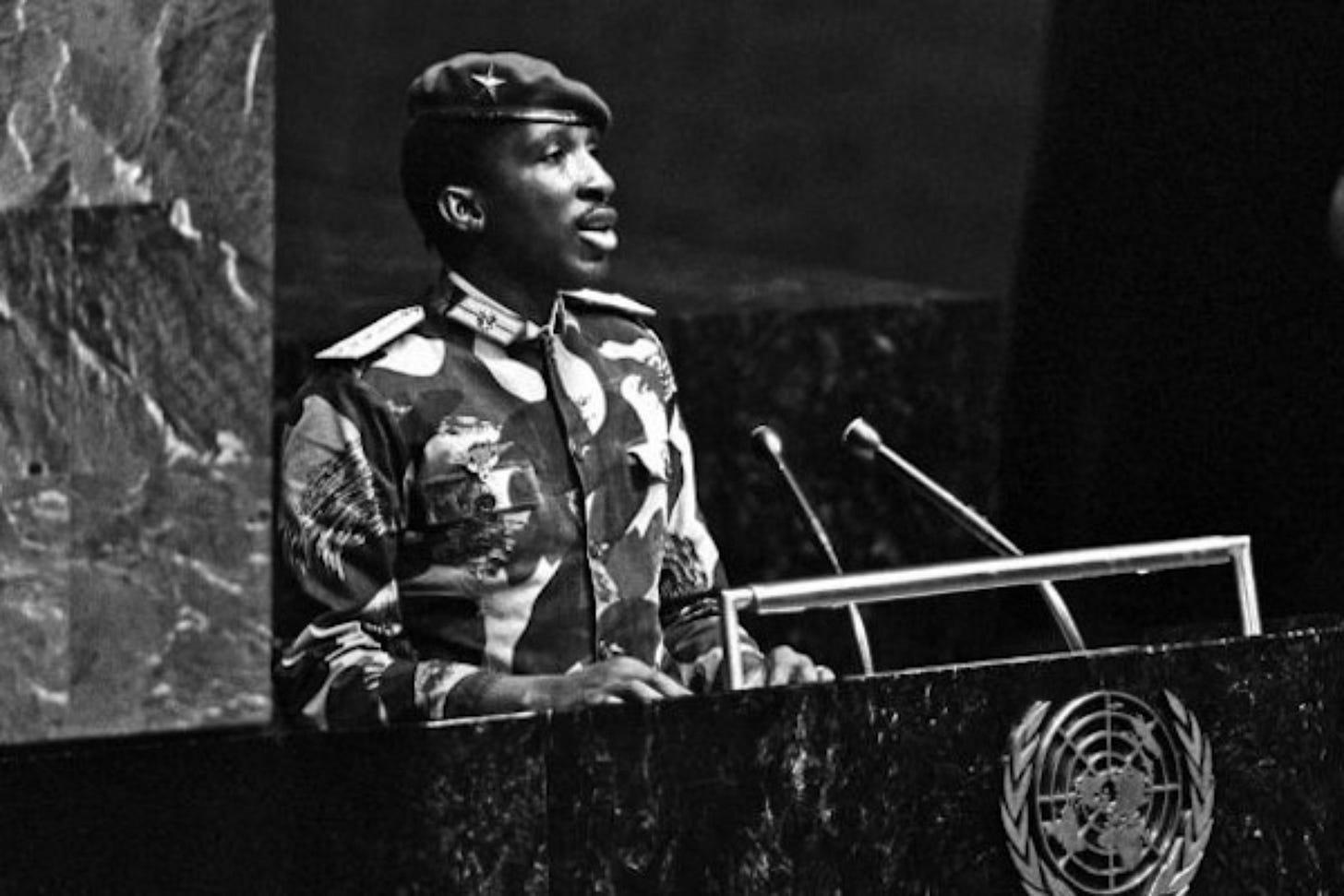

In 1984, a young African president stood before his people and asked: “Where is imperialism? Look at your plates when you eat. The imported grains of rice, corn, and millet – that is imperialism.” He knew that no flag, no anthem, and no constitution can feed a hungry child. That food delivered with strings attached is not generosity — it is control, not liberation. That man was Thomas Sankara, and he was not alone.

Across Africa, from Accra to Algiers, from Cape Town to Conakry, the message was the same: true decolonisation would be measured not by flags or anthems, but by fields and granaries, by the seeds we plant. Pan-African leaders saw that Western aid, imported food, and structural adjustment were tools of neo-colonial control meant to keep African nations indebted, dependent, and divided. They knew that decolonisation required a radical rethinking of how food, land, and wealth are distributed and controlled. So they set out to break the chains.

Sankara launched sweeping agrarian reforms — redistributing land back to peasants, rejecting food aid, and “demanding tractors, not grain.” Within just four years, cereal production doubled from 800 thousand tons in 1983 to 1,700 thousand tons by 1987. Over 10 million trees were planted. And Burkina Faso became self-sufficient in food. He prioritised women's rights, education, healthcare, and national vaccination campaigns, while nationalising industries and land to break free from colonial control. Sankara proved that with agroecology, rapid progress to improve food sovereignty was possible with strong political will. His vision for a self-reliant Africa, rooted in dignity and sovereignty, threatened Western imperial interests. And for that, in 1987, he was assassinated in a coup backed by France and the United States.

Decades earlier, Patrice Lumumba, on the eve of Congo’s independence in 1960, called for an end to economic exploitation and a return of the economy to the people. Without control over resources and economic sovereignty, he warned, political independence would be meaningless. “The Congo's independence is a decisive step towards the liberation of the whole African continent,” he declared. “I call on all Congolese citizens, men, women and children, to set themselves resolutely to the task of creating a national economy and ensuring our economic independence.” Within months, he was assassinated by a CIA-backed plot.

Kwame Nkrumah built state farms across Ghana, launched cooperatives, and invested in local industries to make the country self-reliant, employing thousands, growing staples, and laying the groundwork for economic independence. His vision reached far beyond Ghana: a united Africa that could feed, clothe and govern itself, free of foreign control. “Seek ye first the political kingdom,” he said, “and all else shall be added unto you.” But like Lumumba, his bold challenge to imperialism made him a threat. In 1966, he was overthrown by yet another CIA-backed Coup that sought to dismantle his economic programs and reopen Ghana to foreign capital.

In South Africa, across the radio waves, Steve Biko taught that resistance wasn’t just protest — it was growing your own food, running your own clinics, building cooperatives, refusing to beg from the hand that beats you. “Black people must be their own liberators,” he said, urging South Africans to reject the colonial mindset and create their own systems of care and sustenance. “The greatest weapon in the hands of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed,” he warned – a reminder that liberation begins with unlearning domination. His vision was in direct opposition to the apartheid’s economic structure, which sought to keep black South Africans dependent on the state. For this, he was murdered by apartheid police in 1977.

Amílcar Cabral, agronomist and guerrilla, understood that revolutions begin on the land. In the rice fields of Guinea-Bissau, he led one of Africa’s most successful liberation movements — not just with weapons, but with seeds, tools, and organising. “The people are not fighting for ideas,” he said, “They are fighting to win material benefits, to live better and in peace, to see their lives go forward, to guarantee the future of their children.” During the war, the areas liberated by his PAIGC movement set up their own fields, village schools, and health posts. Cabral, ever the agronomist, taught farmers better techniques and improved rice strains even as bullets flew. It was clear that food sovereignty and self-determination were inseparable. “Tell no lies, claim no easy victories”, he warned, knowing that real liberation could not be donated through aid or charity. In Cabral’s eyes, the easiest victory of all is one handed down by the very powers you’re fighting. True liberation would require the hard work of ploughing, planting, and planning for the long term. In 1973, just months before Guinea-Bissau declared its independence from Portugal, Cabral was assassinated in a plot widely believed to be backed by the Portuguese secret police.

While the names of male Pan-Africanists often fill the pages of history, the movement itself has always been fed, organised, and sustained by women. From Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti who led mass protests against colonial taxation and patriarchal rule in Nigeria, to Josina Machel who mobilised women and youth in Mozambique’s liberation struggle, to the defiance of Queen Nzinga who led military resistance against Portuguese colonisers for decades, to Miriam Makeba, whose voice carried the pain and pride of South Africa’s anti-apartheid struggle across the world — African women have not just joined liberation struggles, they have shaped them.

One such figure is Nyéléni, a legendary Malian peasant woman whose life and legacy have become a symbol of food sovereignty and women's resistance. Nyéléni's story, passed down through generations in Mali, tells of her exceptional farming skills and her defiance of societal norms that relegated agriculture to men. She not only competed with male farmers but often outperformed them, cultivating crops like fonio and samio in arid conditions, thereby feeding her community and challenging patriarchal structures. Her prowess in agriculture and her role in sustaining her people made her a symbol of resilience and self-reliance. In 2007, her legacy was honoured when the first international forum on food sovereignty was named after her—Nyéléni. Held in Sélingué, Mali, the forum brought together over 500 delegates from more than 80 countries, including peasants, fishers, pastoralists, and indigenous peoples, to discuss and strategise on achieving food sovereignty. From this historic gathering emerged the Declaration of Nyéléni, a landmark political statement that defined food sovereignty as the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food systems. This September, the lineage continues. Movements from around the world will convene once again — this time for the third Nyéléni Forum in Sri Lanka — to reimagine the future of social justice and systemic transformation, in a world still shaped by colonial greed and corporate extraction.

Any future worth building must carry that lineage forward, rooted in the legacy of women like Nyéléni, and in the knowledge that food, freedom, and revolution are bound together by the hands of those who have always nourished life.

THEY TRIED TO BURY US — BUT FORGOT WE WERE SEEDS

While our revolutionary ancestors were overthrown and assassinated, they were not erased. Today, a new wave of leaders and movements across Africa are reincarnating that truth. As the Western empire teeters on the brink of collapse, its arrogance laid bare for the world to see, communities long dismissed as the “Third World” are boldly asserting themselves as the Majority.

They are not asking for permission. They are reviving the visions of their forebears and grounding those dreams in policy. In land. In food. In self-determination. A breaking of chains. A planting of sovereignty. A refusal to imagine the future in the image of the past. This isn’t just political change — it’s a fight to live outside of empire’s control. Because the seeds of sovereignty are sown in our own soil.

And that future is now. In the last few years, a wave of political transformation has swept through West Africa’s Sahel. Governments once seen as puppets of Paris or Washington have been overthrown by popular uprisings. Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger — three nations bound by history and struggle — have each undergone coups, replacing Western-backed elites with youth-led, defiant, and explicitly anti-imperialist leadership. In Senegal, the 2024 electoral shift brought a new government committed to breaking from French influence. Even in Ghana, where changes come more cautiously, efforts are underway to reclaim control over finance, mining, arms, and foreign policy. The tide is turning.

African leaders are voicing what their people have long known. That peace does not mean liberation. That foreign aid was a noose. And that independence was never truly won.

No figure embodies this shift more than Captain Ibrahim Traoré of Burkina Faso, whose speeches have become quite popular across social media — inspiring celebration and solidarity among supporters, and speculation among sceptics, even as on-the-ground reporting remains difficult to verify. At just 34, he became the world’s youngest head of state — and to many Burkinabè, the second coming of Sankara. Since taking power in 2022 amid mass protests against French failure and extremist violence, Traoré has moved quickly, expelling French troops and shutting down colonial institutions. And in 2025, he made one of the boldest moves in African history: the nationalisation of all land.

“Land now belongs to the State,” his administration declared. Foreigners are banned from rural ownership. The land will serve the Burkinabè people, not the pockets of the West. But the vision Traoré is evoking, whether fully realised or still in formation, goes deeper than land titles. It’s about how the land is used — and who it feeds. Because there is no liberation without food sovereignty, he armed the farmers. In a push to turn Burkina Faso into a regional breadbasket, his government distributed over 400 tractors, 239 tillers, and 710 water pumps to be distributed to cooperatives and smallholders.

He rejected the West’s debt traps, refusing IMF and World Bank loans. “Africa doesn’t need the World Bank, IMF, Europe or America,” he declared. Burkina is now seeking investment on its own terms — from Africa and the Global South — breaking the cycle of debt-for-export dependency.

He invested in local production. Burkina opened its first tomato processing plants, a gold refinery, and new cotton mills, ending the colonial logic of exporting raw materials. Keeping wealth in-country, lowering prices, and creating local jobs.

And finally, he is restoring national pride. Colonial court wigs were banned. Judges now wear traditional Burkinabè dress — a symbolic shift, but a powerful one. Because the movement Taroré is leading is not just economic or political. It’s cultural. It is a reclamation of identity, dignity, and direction, rooted in the soil and in the people who till it.

”Together, in solidarity, we will defeat imperialism and neo-colonialism for a free, dignified and sovereign Africa.” - Captain Ibrahim Traoré

Whether his administration will fulfil this promise remains to be seen. But what’s clear is that the hunger for sovereignty over land, food, and futures is erupting. And Traoré has become a vessel for that longing. Though he may not speak the language of agroecology or food sovereignty, the message he embodies — of reclaiming land, feeding ourselves, and breaking from dependency — is resonating. From African youth sharing his speeches to global icons like Burna Boy and Ronaldo expressing support, the symbolism is going viral. And movements should take note: this is evidence that the call for sovereignty is not just relevant — it’s popular.

And it’s working.

Markets in Ouagadougou are reportedly filled with local produce. School meals are being made with Burkinabè-canned tomatoes. And across the region, the revolution is spreading. In Mali, there’s talk of mirroring the land reform and doubling down on local rice production. Niger's new government is actively renegotiating mineral deals to assert greater control over its natural resources. In June 2024, the military junta revoked the operating license of the French company Orano at the Imouraren uranium mine, citing unmet development expectations. This move signifies Niger's intent to end preferential treatment of foreign entities and ensure that the extraction of its resources benefits the nation more equitably. The Malian government has taken similar action in re-negotiating the contract for revenue sharing with the Canadian Barrick Gold company.

Together, the three nations have formed a mutual defence pact — the Alliance of Sahel States (AES) — a promise to stand together against foreign interference. When ECOWAS and Western powers threatened to intervene after Niger’s 2023 coup, Mali and Burkina stood in solidarity, declaring “An attack on one, is an attack on all.” Echoing a long-held Pan-African dream: a united Africa in defence, economy, and purpose. Most importantly, the people are with them. Across Bamako, Niamey, and Ouagadougou, you see celebrations, not protests. French flags are being burned in public squares with chants of “Nous Sommes Independants”, (France Must Leave).

There are still challenges. The Sahel faces insurgency, climate shocks, and poverty. These are military juntas, not elected governments — and critics warn of authoritarianism. But the truth remains: Western-backed regimes had decades to prove themselves. And they failed.

History is in motion. And the rains have begun.

THE DAMS ARE BREAKING

This moment is not purely African – it is part of a broader global shift. As the Western imperial order grapples with its own authoritarianism and inevitable collapse, the Majority World* is reclaiming its power.

The Genocide in Gaza has shattered the West’s once-unquestioned moral authority. Their self-righteous lecturing has given way to deafening silence. It’s hypocrisy laid bare. It’s double standards, exposed. The Majority World* sees this and is now carrying the banner of human rights.

*Majority World refers to the countries commonly labelled as “developing,” who in fact make up the majority of the world’s population. Minority World refers to the countries commonly labelled as “developed,” and emphasises that while these countries tend to impose their will on the rest of the world, they are, in fact, the minority.

At the same time, the very institutions that upheld the Western worldview are proving impotent and paralysed. The veto power of the UN Security Council is an affront to global democracy. Neoliberal institutions like the World Bank and IMF face crises of legitimacy, their policies increasingly seen as tools of domination, locking communities into cycles of dependency and debt. Today, the unipolar world order is ever fragile.

Multipolarism is accelerating. It’s not just the rise of BRICS as a political bloc— it’s what BRICS represents: a global rebalancing. Originally formed by Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, BRICS has grown to include new members like Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran and the United Arab Emirates, reflecting a broader coalition of nations disillusioned with Western-dominated systems. Together, they are building development banks that operate outside of IMF conditionalities, and piloting payment systems to bypass the chokehold of the dollar and Swift.

Power brokers in the Majority World are asserting themselves: offering security, building trade and shaping their own future. But the greatest threat to Western dominance is not a competing superpower, regardless of what we have been told, but the rise of South–South cooperation.

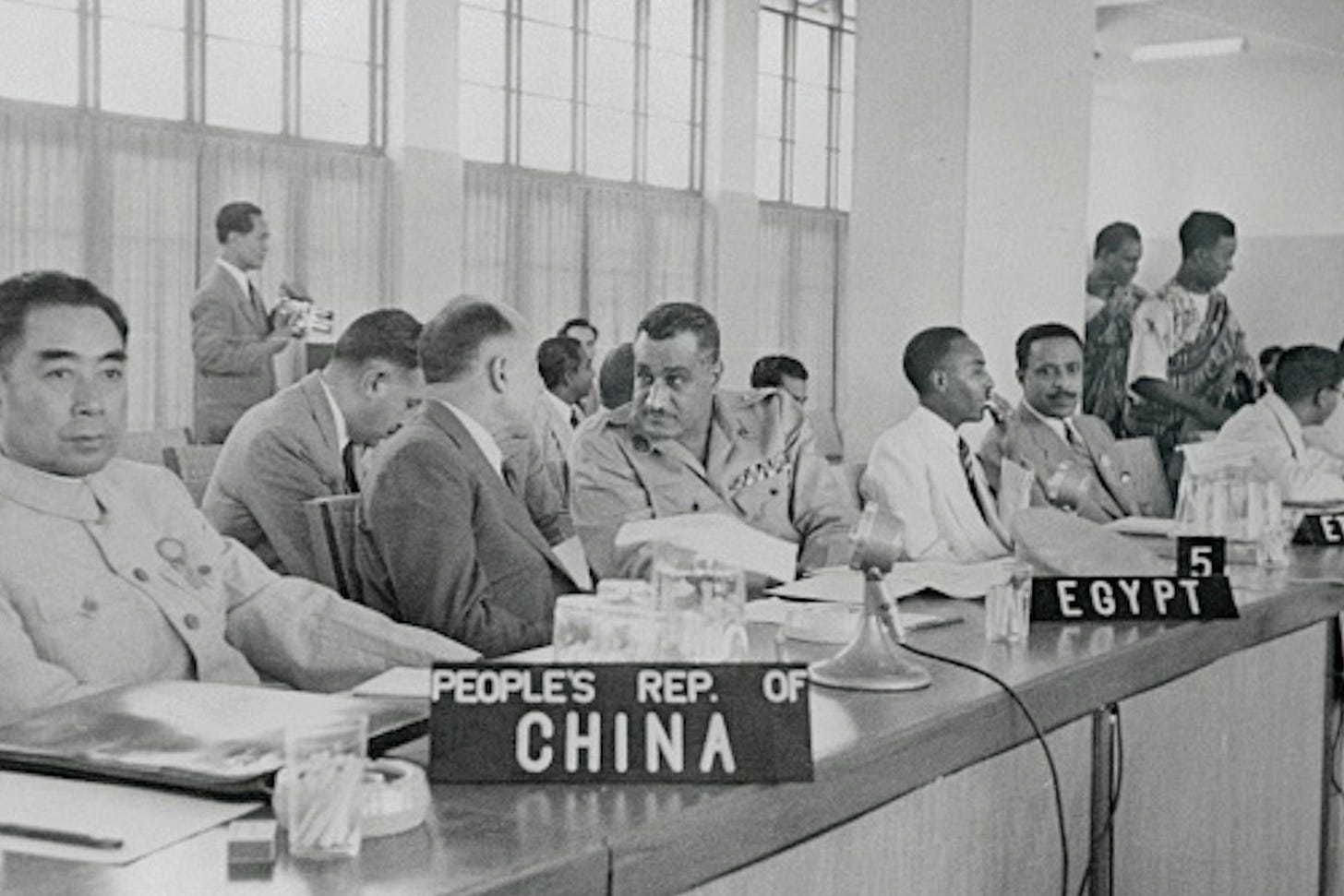

This is what Pan-Africanism stood for. Not just a united Africa — but a united Global South. A world where the colonised rose in solidarity, from Harlem to Havana, Hanoi to Harare. Where the Black Panthers met with African liberation leaders, and revolutionary Cuba sent doctors and soldiers to Angola. Where Bandung imagined a world beyond empire, and the Non-Aligned Movement declared: we will not choose between two masters — we will be free.

Empire has always feared this: the power of the majority united. It’s why they didn’t just assassinate Sankara, Lumumba, Nkrumah, and Cabral — they tried to kill the very dream of Pan-Africanism. Each of them dared to speak of a united Africa, one free from the chokehold of colonial borders, foreign debt, and imperial control. They knew that Pan-Africanism was — and remains — the greatest threat to Western imperialism. And empire knew it too. That’s why they kept Africa divided — propping up regimes, stoking conflict, and weaponising debt. As long as Africa remained fragmented, it could be controlled, exploited, and looted.

It’s the same playbook, again and again. They surveilled, infiltrated, and dismantled the Panthers. They hunted down the Sandinistas, the Mau Mau, and the student uprisings. Then — and now — the tactics remain the same. Discredit, divide, dominate. Label resistance as terrorism. Sow chaos to justify intervention. Pit the oppressed against one another to maintain control.

Because empire doesn’t represent the many. It only survives when the majority are divided. But that’s changing. What happens when the Majority World begins to speak as one? When the peasants of Burkina Faso echo the struggle of landless farmers in Brazil? When Black farmers in the U.S. see their fight mirrored in the fields of Palestine?

That’s when empire trembles. Because the greatest threat to its dominance has never been force. It’s solidarity.

South–South cooperation isn’t charity. It’s strategy. It’s the quiet revolution of trade, security, and knowledge shared among the once-colonised. And it’s already unfolding—in food systems, in currency realignments, in mutual defence pacts. The Majority World is not rising — it has risen. Now, the question is: will we recognise ourselves in one another, and rise together?

To understand the current state of the world, we must recognise a historical pattern: before empire collapses, its final stage is always arrogance. That arrogance now fertilises the upsurge of far-right movements across the West. But make no mistake — this is not a sign of strength, but of desperation. It is the panic of an old regime that cannot fathom its waning influence — the same influence that orchestrated the violent overthrow of more than 60 democratically elected governments. The same influence that is now withdrawing aid from nations it made dependent.

And in that unravelling lies Africa’s opportunity — and its crossroads. A chance to unite. To dictate its own terms. To experiment with new forms of governance. But none of this will be easy. Imperialism doesn’t vanish overnight. And so the question becomes not just how to break free—but how to stay free.

THERE IS NO LIBERATION WITHOUT FOOD SOVEREIGNTY

There’s a story often told about a man at the crossroads, trading his soul for music. In the American South, it was Robert Johnson. In pop culture, it’s the devil who waits there. But that’s not the whole story — it’s a distortion. In West African and Afro-diasporic spiritual traditions, the guardian of the crossroads is not the devil but a divine messenger. Known as Esu, Elegba, Papa Legba — this Orisha is the opener of roads, the keeper of Ase, the power to make things happen. Trickster, yes, but never evil. He is venerated first because nothing moves without him.

So what if the crossroads isn’t where we sell our soul — what if it’s where we find our path? What if, instead of a site of loss, the crossroads is where we reclaim our power, where the divine speaks, and where transformation begins?

The end of empire can be violent– like a dying beast, it lashes out. But collapse is also a moment of profound possibility. The fall of Western dominance may not be the end of the world; for most of humanity, it may just be the beginning.

In this time of transition, food sovereignty must emerge as the foundation for true liberation.

Imagine a future where the Majority World peoples are truly free to shape food systems that serve their communities, without Monsanto, USAID or the IMF dictating terms. A future where hunger is no longer used as a weapon. Where no nation can be starved into submission by sanctions or structural adjustment, because communities control the land they till. A world of democratic global governance built from the ground up: by networks of farmers, cooperatives, indigenous communities, and people’s organising across borders – not for power, but for life. It would be multipolar. A mosaic. A symphony of many voices, united in their difference.

Food sovereignty – the right of people to define their own food and agriculture systems – is a unifying tenet in this moment. It is both practical and profound. As Thomas Sankara said, “Those who feed you – control you.” And so, food sovereignty means power. The power of choice in the hands of the people. It means reclaiming the land. Building grassroots economies. Feeding ourselves with dignity. It means a world where everyone has a seat at the table. And now, the message is spreading — sometimes without using the words. From smallholders defending their seeds to new leaders challenging dependency, the call for food sovereignty is travelling under many names. The challenge ahead is not only to defend the principle, but to recognise its messengers — even when they don’t speak our language.

So let us be hopeful, but let us also be prepared.

The post-imperial future will not arrive as a gift; it must be built deliberately, collectively, with vigilance against new forms of domination.

So, in Africa and beyond, new leaders will face a test: Will they decentralise their authority to enable local sovereignty, or will they consolidate more power? In the Sahel, will growing civil conflicts push governments toward militarisation at the cost of investing in education, healthcare, and rural development? The presence of popular support today must evolve into participatory governance tomorrow — lest today’s liberators become tomorrow’s oppressors. And this future must be shaped by those who have long carried the heaviest burdens — women, peasants, Indigenous communities. Not token inclusion, but real power. The African philosophy of Ubuntu — the ethic of shared humanity and mutual care — offers a vital foundation for decolonising governance and reclaiming sovereignty. Thinkers like Ki Zerbo, Mandela, and Bachir Diagne remind us: Africa’s path forward must be collective, not extractive; cultural, not just political. Ubuntu once helped heal a fractured South Africa — today, it can unify a continent.

Decolonisation is not a single event. It’s a living praxis. A constant unlearning.

Still, how can we not feel hopeful?

The shackles are breaking open. The myths told to keep us complicit — that we cannot govern ourselves, feed ourselves, chart our own path — are falling apart at the seams.

From the small farmers saving seeds, to the youth chanting Sankara’s name on the streets, to the elders who remember the day Lumumba declared Congo’s independence, there is a generational bridge now. A sense of return. Of the rising sun. The spirits of the ancestors and the dreams of the young have become one.

Liberation is not just resistance — it is the radical act of birthing new worlds. Of breaking the cycle of generational trauma. It is the drumbeat of women sowing seeds, of midwives and mothers nurturing life, where empire only brought death.

This is the moment of harvest. The dreams sown by our fallen comrades are ripening in the present. Their courage and sacrifice were not in vain. We, the Majority, are beginning to reap what our ancestors sowed. And this time, it is all of us – or none of us.

The road ahead will be hard. But we walk together. With humility. With audacity. With love.

Let the future be built not on the empty promises of empires, but on full plates of shared harvests.

As the empire writes its final chapter in arrogance, ours remains unwritten, and full of possibility.

This documentary that traces how the U.S. and Belgium orchestrated the 1960 coup against Congolese Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba and his efforts to create a United States of Africa, using not just politics and propaganda, but music. The film exposes how cultural soft power was weaponised during the Cold War to undermine African liberation movements.

This article on the sentencing of Blaise Compaoré for orchestrating the 1987 assassination of Thomas Sankara. It reflects on Sankara’s radical legacy and critiques the decades-long impunity Compaoré enjoyed under the protection of foreign powers. The trial is more than a reckoning with murder — it’s a confrontation with the global forces that opposed Sankara’s politics. The article affirms that while they killed the man, his revolutionary project remains alive in the hearts of Burkinabe and Africans.

This video coverage of the African Unity Walk with Traoré held in Ghana, May, 2025, which carries the spirit and hopes for liberation across the continent.

Upgrading to paid isn’t just about supporting this newsletter, but also resourcing all of our other work to resource movements around the world. If you have found value in these words and ideas, and you are in a position to become a paid subscriber or to donate directly to our organisation, we would be so grateful for your support

As always, thank you for reading.

Every resource produced by A Growing Culture, whether a newsletter, article, post, or design, results from countless hours of research, reflection, and the synthesis of profound conversations held both within our team and with our partners and comrades. Behind the scenes, a wealth of effort goes into making these conversations happen, from overseeing our day-to-day operations, securing our funding, to forging deep relationships with communities around the world who are leading food systems transformation. These relationships fuel our thoughts, inform our words, and inspire our actions.

We recognise that no single person can take credit for the work we collectively produce, which is why we prefer to sign as an organisation rather than as individuals. We believe that no idea is inherently our own and welcome anyone who sees value in our work to translate it, build upon it, adapt it to their own contexts, or share it however they see fit.

#This was insightful, truly. Thank you.

Excellent follow up to your previous article. This information used to be so much harder to come by and to some degree still is. Having you, a journalist who is also an agriculturalist, take on the challenge of connecting the pieces is absolutely needed to help people understand our complex food and political history. Thank you. I also appreciated the references, including the documentary. It was put on my watch list.