Every time there’s an economic downturn or crisis, the conversation around inflation resurfaces. Especially since the pandemic, the topic has become something of a buzzword, always lingering in the back of everyone’s minds. The idea of inflation can be daunting because we can’t really see it, but all of us can feel its effects. Like a ghost haunting the economy, we can feel invisible hands picking at our pockets, slowly draining us of our wealth and our standard of living. Just when we think we’re catching up to the “cost of living”, everyday expenses like rent, food, fuel, medicines, and transportation get more and more expensive, and we find our money unable to stretch as far as it used to. But, despite being aware of inflation’s existence, it’s easy to feel powerless to confront it, because it seems like the product of uncontrollable and natural forces.

For the most part, at least as individuals, inflation is out of our control, because it is the product of an industrial system that is coordinated at a global level by governments, international institutions, and transnational corporations. But there is nothing natural about the degree of inflation we’re currently experiencing. In fact, given the disproportionate impacts of inflation on different sections of society, it could even appear like an orchestrated phenomenon designed to systematically favour the few while impoverishing the many.

WHAT IS INFLATION?

First, let’s break down inflation, and how it works. In the most general sense, inflation refers to the sustained increase in all prices across all sectors of the economy.

From the supply side, any disruption in the supply chain or increase in the cost of production of goods and services, whether it be the cost of inputs such as raw materials, the cost of labour, logistical costs, or the profits derived from the sale of goods, can all contribute to the increase in prices. This is referred to as “cost-push” inflation.

From the demand side, inflation occurs when the overall demand for goods and services in an economy is increasing at a faster rate than the economy’s ability to produce them. This could happen due to several factors including: a general rise in consumer demand, an increase in the supply of money from the central bank through measures like printing more currency (when everyone has more money, they tend to demand more goods and prices will subsequently rise), lowering credit interest rates (as it’s less expensive to borrow, consumers can borrow more money at less cost, and thus buy more goods), or a government stimulus like a tax cut (as it increases consumers’ disposable income). All of these could lead to an increase in demand that exceeds the supply of goods or services available, resulting in higher prices. This is referred to as “demand-pull” inflation.

Generally, inflation is calculated by picking a basket of essential goods and services that are representative of what people spend money on in the economy. Since some goods are more essential than others (such as food and fuel), we give them more weight in the calculation. When all these prices are factored into the basket, the result is a price index, depending on which point of production the prices are calculated at, is known as the Consumer Price Index (CPI) or the Wholesale Price Index (WPI). The rate at which this price basket of essential goods changes is the inflation rate.

Take eggs, which have become the poster child for food price inflation in the U.S. Many costs go into the sale of every egg we consume — from setting up infrastructure for chicken farming such as cages and sheds, to acquiring chicks, feeding them, vaccinating them against diseases, powering and maintaining the facilities, paying the wages of workers, processing, packaging, transportation, retail, marketing, and the profit at each stage of production. In theory, an increase in any one of these costs (say an increase in the cost of chick feed), or even an external disruption (like a mass outbreak of chicken flu or an increase of money supply in the economy that leads to more demand for eggs) could inflate prices. Since eggs are so fundamental to many of our diets, the prices of all products related to it — egg-based mayonnaise, custards, puddings, waffles, and cakes — will also increase.

Given how complex and globalised the industrial food system has become, most governments, economists, and policymakers argue that some amount of inflation is inevitable. Naturally, the argument goes, unforeseen events or changes in any one of the links along a vast, interconnected supply chain will have an impact on costs and, therefore, final prices.

Most of the recent inflationary pressures have been primarily driven by “cost-push” factors such as global supply chain disruptions and increasing input costs, rather than “demand-pull” factors such as increases in money supply or decreases in interest rates. For this Substack, we will mainly focus on the supply led factors that are driving global inflation.

WHAT’S “NORMAL” INFLATION?

The U.S. Federal Reserve argues that some amount of inflation is a sign of a strong economy. Deflation, they say, means low economic growth. The Federal Reserve has not established what an “acceptable” rate of inflation is. However, as they state, “policymakers generally believe that an acceptable inflation rate is around 2 percent or a bit below”.

So what does inflation look like for eggs? According to the US CPI, the average price of eggs in the US increased by 60% in 2022.

And while we tend to hyperfocus on the price of individual goods (like eggs), the reality is that when inflation hits, it tends to ripple across all sectors of the economy, until the general prices of all commodities in the economy adjust to the inflated rate. It’s not just eggs that have seen a massive price increase.

Flour is up 23%. Lettuce is up 25%. Butter is up 35%.

In the last few years, global food prices have been rising astronomically.

Of all sectors, inflation tends to hit the agricultural sector the hardest, because food is the most basic necessity that impacts all of our well-being. Inflation in essential foods has a domino effect across the economy, causing impoverishment and hunger, particularly among vulnerable groups who are deprived of the access and resources required to cope with rising food costs.

As of March 2023, food price inflation is at 19.2% — the highest it’s been in 45 years. This is no small number — we haven’t paid this much for food since 1977.

Inflation at these rates has had devastating consequences for millions of people, who are now facing the threat of hunger due to the increased costs of essential food items every year. The Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO) estimates that in 2020 alone, 928 million people were severely food insecure — a rise in one (pandemic) year that was larger than the previous five years combined. In the same year, approximately 1 in 3 people — 2.37 billion — did not have regular access to adequate food.

ARE WE “ALL IN THE SAME BOAT” WHEN IT COMES TO INFLATION?

Given the state of the economy, it’s no surprise that consumers worldwide are frustrated with inflationary forces, and many of us are demanding more affordable food prices. As our frustration with these forces continues to fester, it’s normal to seek out sources that will help explain why inflation occurs, how it is affecting us, and how we can mitigate its effects. Countless books, papers, and articles are released every year unpacking the concept and offering explanations.

However, the most visible narratives on inflation tend to be produced or endorsed by transnational corporations, who claim to have the deepest insights into market conditions. These corporations often put out messages asking for economic solidarity and cooperation, suggesting that we are “all in the same boat”, and we have to “weather through the storm” together. They assert that they too are hurting because of the crisis — that they’re struggling to make profits, as their operating costs, especially workers’ wages, are already so high and rising. That they have no choice but to either increase their prices, decrease workers’ wages, or shut down. You might have seen some of these headlines:

These narratives have been historical in creating tensions between consumers, small-scale producers, and workers, and pitting them against each other in the market. People with genuine fears about inflation are made to believe that workers’ wages are at odds with their interests, and that efforts to unionise or increase bargaining power must be curbed in order to mitigate inflationary pressures.

But, the market makes it so that consumers, workers, and small-scale producers all receive the short end of the stick from inflation. While workers fight for fairer wages, producers fight for fairer farmgate prices, and consumers fight for fairer retail prices, none of these parties benefit from the billions generated through their economic activities.

WHERE DOES ALL THE MONEY GO?

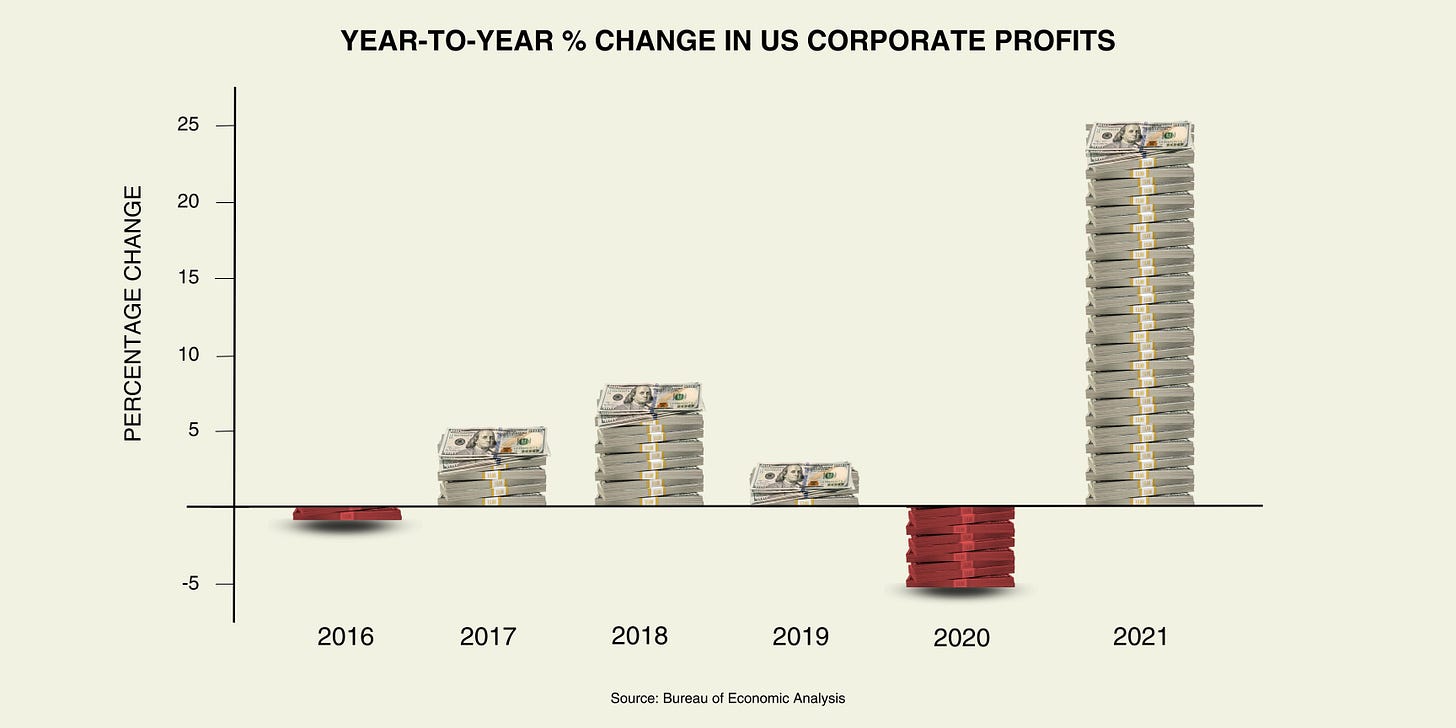

While prices and hunger continue to rise, agribusinesses have made more profits than ever before.

2021 was the most profitable year for big corporations since 1950, with pre-tax profits rising to $2.5 trillion.

Food industry behemoths such as Cargill, Walmart, ADM, Bunge, and Louis Dreyfus reported record profits, with Cargill alone recording its largest profit in history.

Meanwhile, workers have only been getting more and more impoverished.

In recent years, there has been a significant push, championed by figures like Bernie Sanders, to raise the U.S. minimum wage to $15 per hour. This initiative has faced huge resistance, with many arguing that raising wages would cause more inflation.

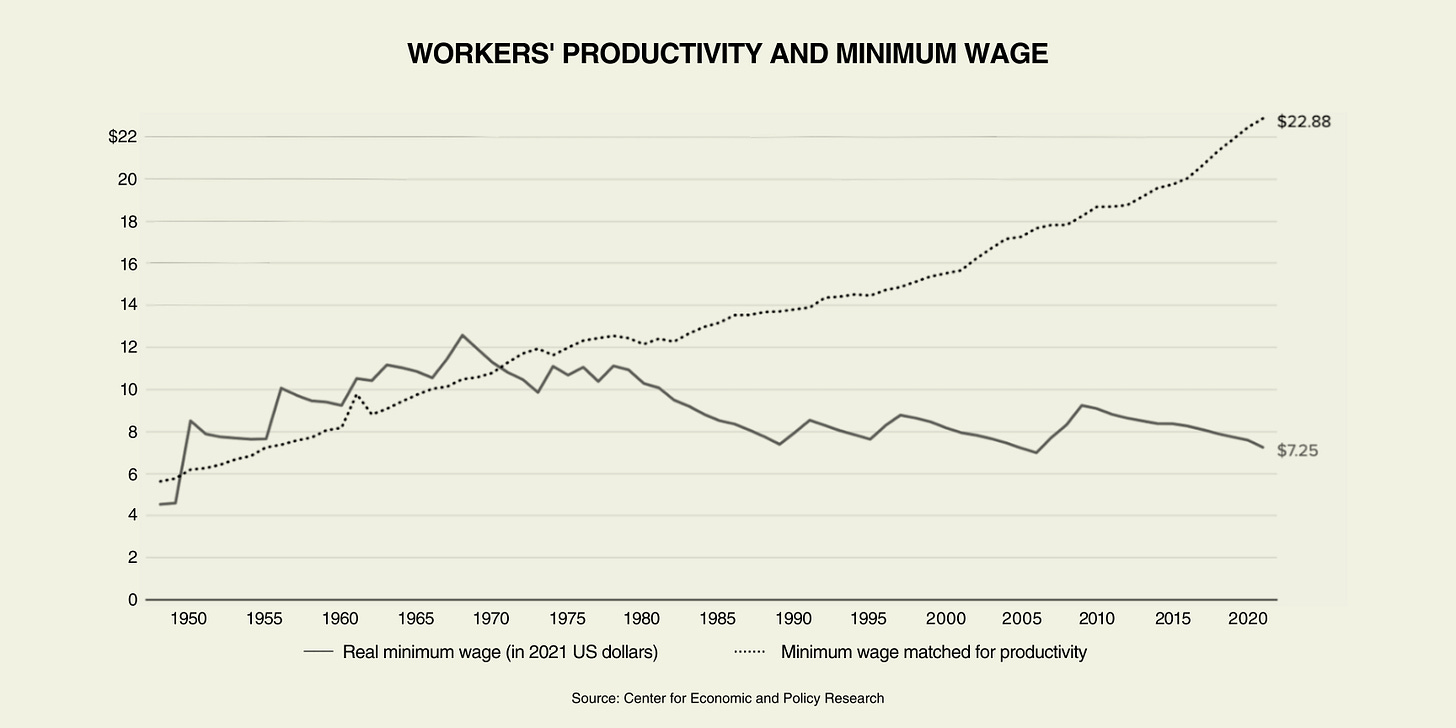

However, if we look at the relationship between minimum wage and inflation, we can see that minimum wage today gives workers the lowest purchasing power since 1955.

Worker productivity (the amount of wealth that workers are generating for corporations), on the other hand, has continued to increase. If we look at the relationship between the amount of money workers are making corporations and the amount they’re getting paid for that work, we see a steady downward trend

If wages kept up with inflation and productivity growth over time — that is to say, if wages not only allowed workers to maintain the same standard of living, but also enabled them to benefit from the economy getting wealthier as a result of their productivity, the minimum wage would be over 24 dollars today.

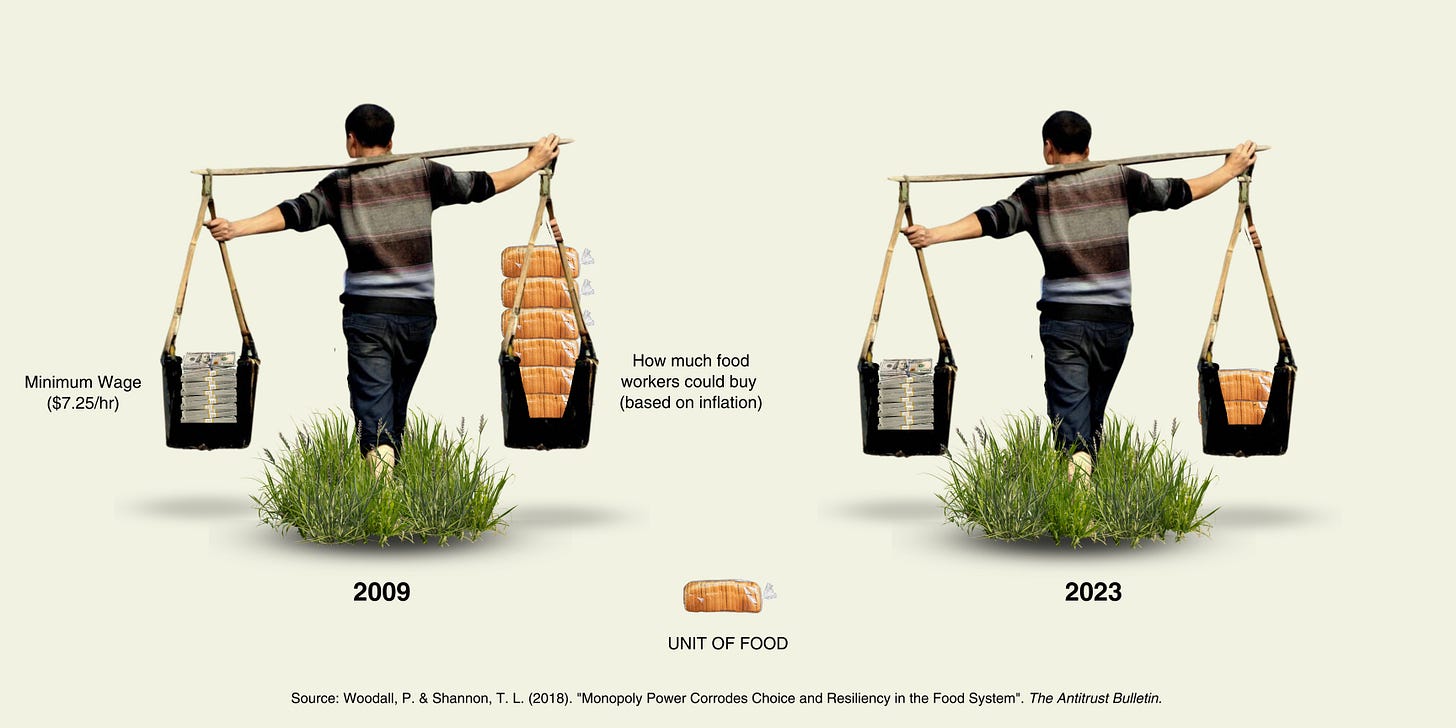

Since 2009, the federal minimum wage in the U.S. has remained unchanged at $7.25 per hour. However, from this period to today, real consumer food prices have risen about three times faster than typical wages, which means that workers have significantly less purchasing power and a lower quality of life today than they did 12 years ago.

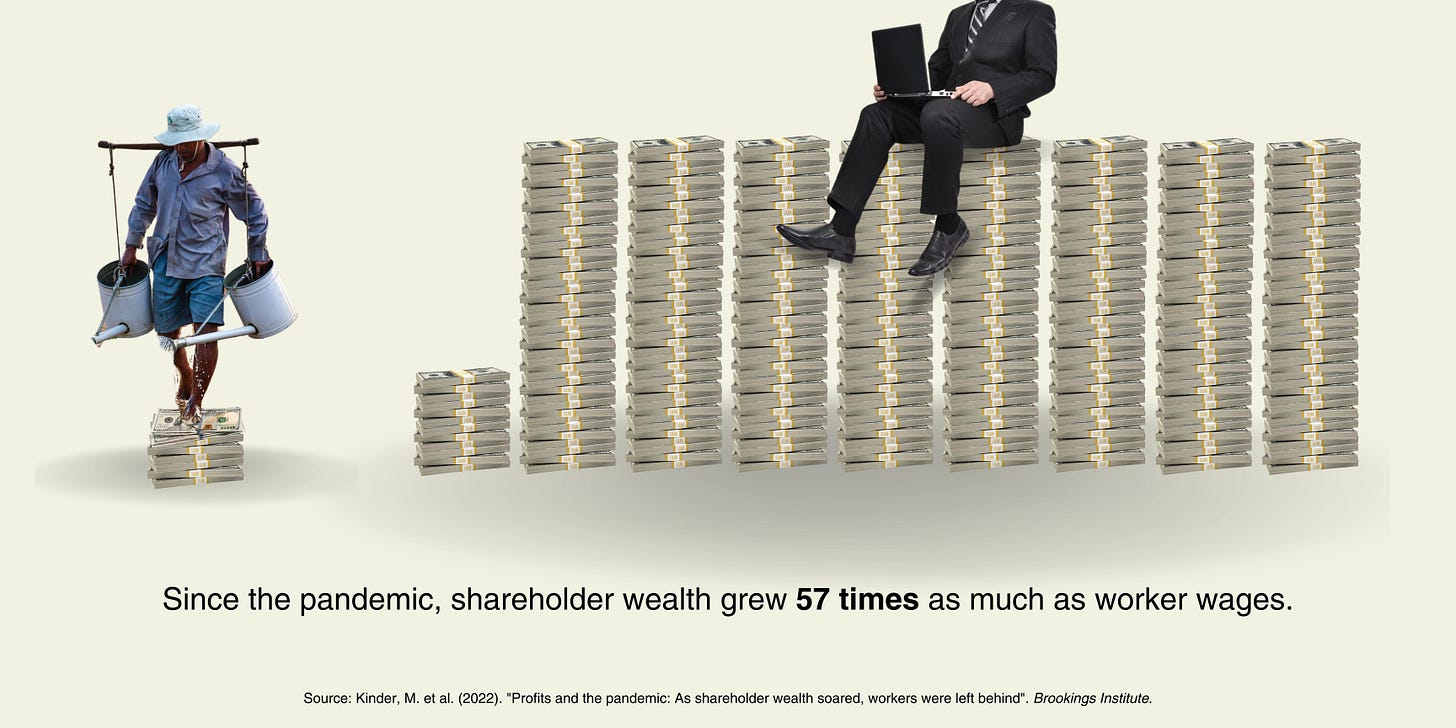

Since the pandemic, shareholder wealth has grown over 57 times as much as worker wages.

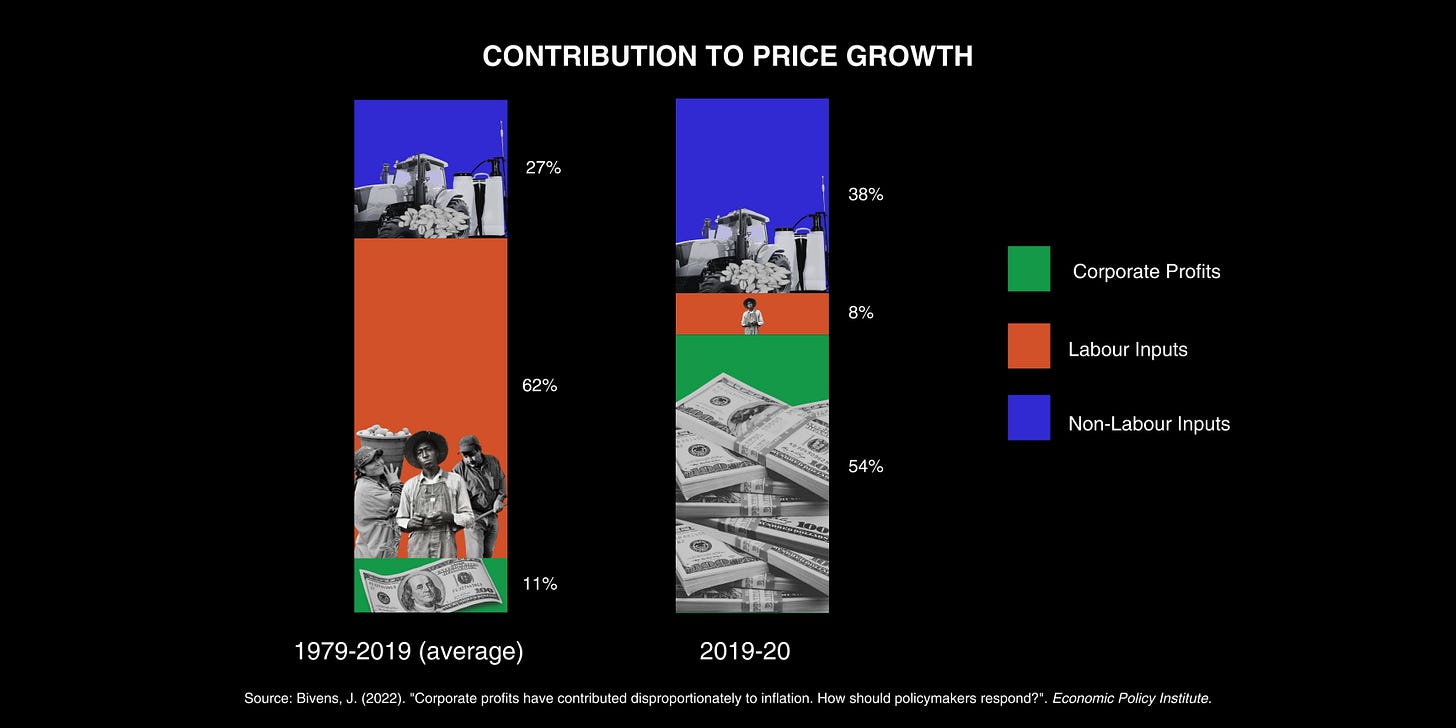

But the inequality goes even deeper. Until before the pandemic, increases in prices could at least be partially attributed to wages rising. From 1979 to 2019, profits only contributed about 11% to price growth, labour costs over 62% and non-labour input costs around 27%. But, shockingly, in the last two years, around 54% of price increases have been driven by profit margin gains, while wage increases were responsible for less than 8% and other input costs 38%. In other words, wages today barely have an influence on prices at all.

According to a study by the Economic Policy Institute, even in the worst case scenario, if the minimum wage is increased to $15 by 2027, and all the extra pay is passed on to consumers as higher prices, the effect on inflation would be very small — only about 0.1% per year. After five years, the inflationary effect would return to 0%. Even this extremely mild inflation could be substantially reduced with a slight decrease in the exorbitant share of corporate profits today.

This is to say, if the share of corporate profits influencing inflationary pressures were decreased more significantly, there would be more than enough room to offer substantially higher wages (well above $24 per hour) with barely any impact on inflation at all.

WHAT’S ACTUALLY CAUSING INFLATION?

The evidence presented above overwhelmingly proves the innocence of workers in driving inflation. Nearly all the inflation we’re currently experiencing is driven by profit margin gains — a phenomenon that is being widely referred to as “greedflation”.

However, corporations didn’t suddenly become greedy overnight. They have always been hungry for profits. So what has changed in the economic conditions today that enables them to extract a larger share of production (or profits) than ever before?

The first reason why corporations are able to retrieve larger profit margins is due to consolidation.

When economists see that four companies control 40 percent or more of a market, they typically label it as an oligopoly, meaning the sector is owned and controlled by a few suppliers. Unfortunately, the food sector is one of the most consolidated sectors globally, with just four firms controlling 60-90 percent of the market.

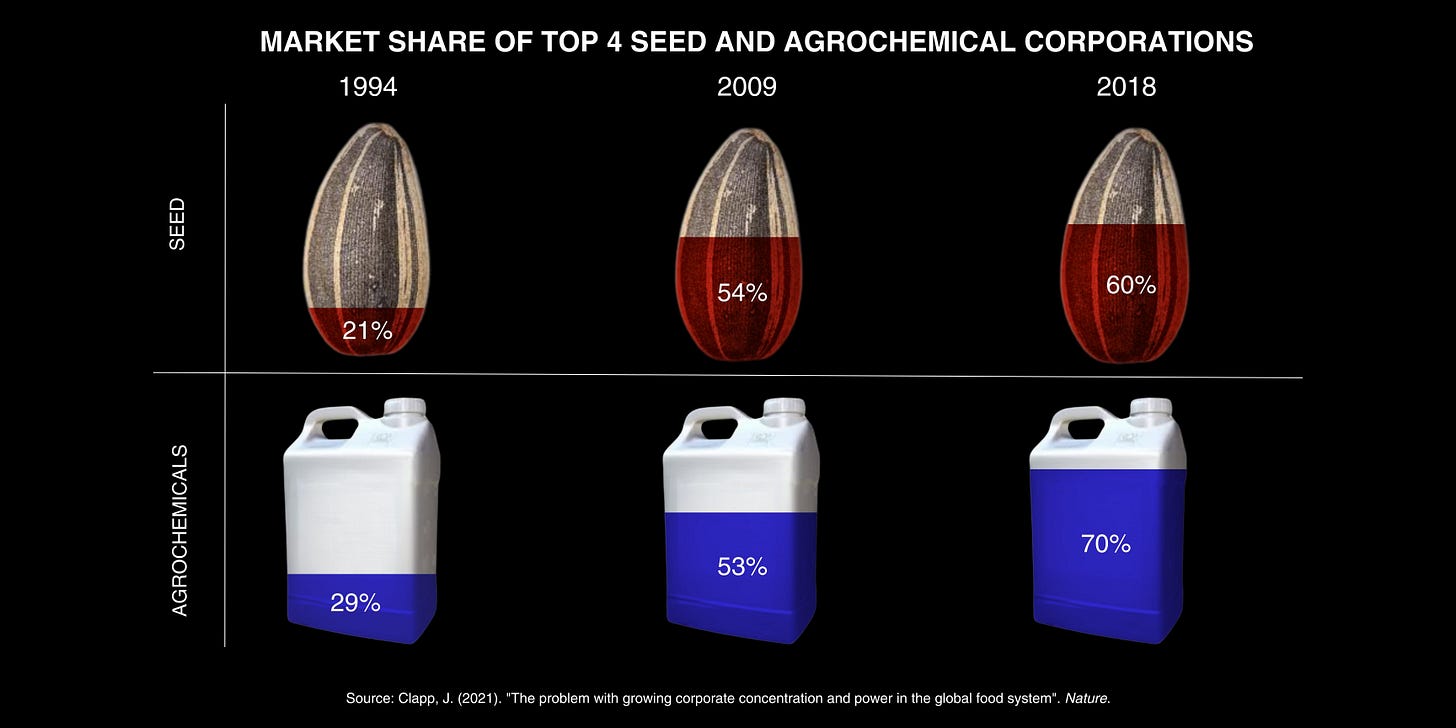

In 1994, four companies (Bayer, Corteva, ChemChina-Syngenta and BASF) controlled 21% of the seed market and 29% of the agrochemical market.

In 2009, they controlled 54% of the seed market and 53% of the agrochemical market.

Today, they control 60% of the seed market and 65% of the agrochemical market.

Four corporations (ADM, Bunge, Cargill and (Louis) Dreyfus) control nearly 90% of the global grain trade.

Five corporations (BASF, Bayer, Dow, DuPont, Monsanto and Syngenta) together control over 75% of all private sector research and development in the food sector.

Today, the food system is so overwhelmingly consolidated that a handful of corporations impose their will on all of us — virtually every farmer, worker, and consumer. Since the onset of neoliberalism, the rate at which the food sector is being consolidated has accelerated rapidly, enabling these corporations to dictate prices, influence policy, and drive scientific research. With their outsized control over the $8 trillion agricultural economy, they are now able to inflate the prices at will, without any repercussions to their bottom line. Consolidation is, without a doubt, the primary driver of food price inflation today.

The second reason for the increasing profit-based food price inflation today is closely related to the first, which is rising input costs.

Before the Green Revolution, farmers operated with a high degree of autonomy and interdependence, relying on the free exchange of knowledge, seeds, and farming techniques. They specialised in creating their own organic inputs (seeds, organic fertilisers and compost, natural insect and pest repellents, etc.) for their production needs. But with the imposition of industrial farming, these traditional practices and knowledge systems have been lost to the majority of farmers. As a result, farmers have increasingly shifted towards purchasing expensive seeds and fossil fuel-based chemical inputs for cultivation, creating a greater dependence on seed and agrochemical corporations. So what has that meant for prices?

From 1979 to 2019, non-labour input costs (such as chemical fertilisers, pesticides, and farm equipment) contributed around 27 percent to prices.

In the last two years (2021-2023), however, those input costs have contributed 38 percent.

While this surge can be partially attributed to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which created a shortage of chemical fertilisers in the market (due to Russia's status as a leading exporter of fertilisers), the major cause is the consolidation of the agricultural input market, and the subsequent increases in prices. According to an article by GRAIN, between 2021 and 2022, these companies increased their profit margins by a staggering 36 percent.

(For more on the effects of the War on Ukraine on global food systems, head here.)

As the agricultural industry becomes more consolidated, the consequences are twofold: Firstly, disruptions such as wars or economic crises can lead to the collapse of entire supply chains, causing significant disruptions to the availability of agricultural inputs and food supply at large. Secondly, consolidation allows corporations to exert greater control over input prices (raising prices at will), as reduced competition limits market forces that would otherwise keep prices in check.

The increases in input costs are indicative of farmers’ growing reliance on corporations for their production needs and ultimately, the erosion of their sovereignty. By systematically pushing farmers towards dependence on inputs, corporations can now extract profits directly from the point of production rather than waiting until the point of sale. This has led to further inflation of food prices, as corporations can manipulate input costs to maximise their profits.

The third reason for corporations being able to get greater benefits from inflation is because of agflation.

Agflation refers to the increase in the price of food relative to other commodities, due to increased demand for non-food related agricultural products such as biofuels and animal feed.

Today, enough food is produced globally to feed 10 billion people. But over 2 billion do not have regular access to adequate food. The industrial food system, which uses the vast majority of the agricultural resources (land, water, fossil fuels), actually only feeds 30 percent of the world. (70 percent of us are fed by small-scale farmers and peasant producers.)

Part of the reason why the industrial food system uses such a disproportionate amount of resources and feeds so few people is that over a third of the food produced by the industry is redirected towards producing non-food commercial goods like biofuels, while the other third gets wasted along the vast industrial supply chain. Despite the inefficiency and wastefulness involved in producing biofuels, it is more profitable to produce than food due to its high industrial demand and the increasing government incentives to transition away from fossil fuels.

The misappropriation of food to feed the production of industrial goods rather than people reduces the amount of food available for human consumption. This, in turn, leads to an increased competition for agricultural resources, including land, water, and crops. With their greater access to capital, corporations compete for these resources and further exacerbate the supply-demand imbalance, forcing food prices to rise at higher rates than the prices of other commodities, or the general inflation rate.

The fourth and final reason for profit-driven food prices is financialisation.

In the last few decades, there has been a growing involvement of financial actors such as investors, hedge funds, pension funds, and commodity trading firms, in the food and agricultural industry. This phenomenon, known as financialisation, involves the transformation of food into a financial commodity that can be traded and speculated on like any other financial instrument in the market (such as stocks and bonds). These financial instruments enable investors to place bets on the expected future prices of food commodities through the use of a “commodity futures contract”*.

*A commodity futures contract is an agreement to buy or sell a predetermined amount of a commodity at a specific price on a specific date in the future. Commodity futures are often used to hedge or protect an investment position or to speculate (and bet) on the future price of the asset.

The financialisation of food began in the 1990s when investment banks such as Goldman Sachs developed commodity indices that allowed investors to trade in food as a financial asset. But it was not just banks. Large agribusinesses, including Archer Daniels Midland (ADM), Bunge, Cargill, and Louis Dreyfus (also known as the ABCD firms due to the first letters of their names) responded to the growing investor demand by expanding their businesses into financial services. As the largest traders of agricultural commodities in the world, these firms dominate every aspect of the food supply chain, from production to consumption, giving them access to sensitive information that they are not obliged by law to disclose. Through the use of this information, they have manipulated their trade activities to maintain an unfair advantage over their competitors and capitalise on the financialisation of food.

Financialisation didn’t just affect the financial aspects of the food and agricultural industry. It has fundamentally changed the way we grow, process, distribute, price, and consume food. As prices became increasingly driven by the expectations of investors rather than the production of real goods, large-scale projects that generated quick financial profits were favoured, at the expense of sustainable, long-term food system investments. Now that food is lumped into indices that include commodities like oil, food prices have become more volatile and easily influenced by price fluctuations in other commodities.

As a result of financialisation, prices today are determined more by investor expectations than the real production of food.

According to the FAO, 98 percent of commodity futures end without the physical trade of commodities. In other words, most of the trading of food commodities in financial markets is purely speculative and does not involve the actual exchange of physical goods. Despite this, speculation heavily influences food prices, often resulting in high inflation rates, especially during economic shocks such as the 2008 housing crisis, or the COVID-19 pandemic.

Today, while soaring food prices threaten global food security, a handful of large food trading firms, especially the ABCD firms, have been minting billions of dollars in profits through their subsidiaries that are heavily invested in market speculation.

A CRISIS OF INFLATION OR A CRISIS OF CAPITALISM?

The amount of inflation we’re experiencing today is massive. Powerful institutions claim that the spike in prices is a reflection of the rising cost of doing business and the pressures caused by rising worker wages. In other words, they suggest that corporations and workers suffer equally from inflation. This narrative tends to be used to justify driving wages down (or at least not raising them to compensate for increasing prices). They effectively pit workers and consumers against each other, leaning on the assumption that either fair prices or fair wages are possible (but not both).

When we look at the data, however, what we see is something very different: corporations making record-high profits while worker wages stagnate. The stagnation of wages has a simple explanation: there is no political will to justly compensate workers, despite the fact that their productivity (the amount of profit they’re generating for corporations) has continued to increase. We propose that the recent spike in profit rates, and their subsequent inflationary pressures driving food prices to historically high levels, is due to four main factors: the consolidation of control over food system markets, the profit-motivated rise in input costs, the increase in demand for non-food products created through the diversion of crops, and financial food speculation.

Inflation is often presented as an isolated crisis. But it’s actually baked into capitalism’s design. Capitalism stimulates growth through overproduction, where too many goods are produced relative to the demand for those goods, and maintains power imbalances through underconsumption, where workers do not earn enough income to purchase all of the goods and services that are produced. As a result, there is always a surplus of goods being produced without enough people able to afford them, and corporations inevitably experience a falling rate of profits. In order to increase their profits, they respond by either decreasing wages or raising their prices even more, leading to inflation. In other words, the capitalist system has an inherent tendency towards crisis and instability due to the contradiction between corporations’ interest in accumulating more capital in pursuit of profits, and consumers’ and workers’ need for fair prices and wages.

In this sense, inflation can be understood as a distributional struggle over the surplus that different groups of society, including workers, corporations, and governments, produce. As each group competes to maximise their share of the surplus (or in the case of workers, minimise the exploitation of their labour), prices rise, and they try to shift the burden of inflation onto the others. Ultimately, the group with the most influence and power in society is able to avoid the burden of inflation. Since corporations control the means of production they are able to procure the entire share of the surplus (or profits) while shifting the burden of the inflation it induces on workers and consumers.

We’re told that it’s not possible to have both fair prices and fair wages. In this way, narratives around inflation become a tool for sowing division. But what if we recognised that the only reason we can’t have both (fair prices and fair wages) is because of corporate greed? What if we focused our attention on the fact that most of us are losing out, while a few benefit? What if we understood inflation as the natural effect of capitalism’s contradictions? And what if we approached the solution to inflation not by putting patches on our economic system, but instead, confronting its fundamental flaws?

*A Note on Donations

We made the decision not to create a paywall, in keeping with our value of making information open-source and freely available to all.

We have over 14,400 people in our Substack community, and 134 of you have decided to become paid subscribers. At this point, we are not breaking even on the expenses for this publication (the hours it takes to research and write cost more to the organisation than the donations we receive). Our aspiration is to eventually break even and become a fully reader-supported publication.

If you have found value in these words and ideas, and you are in the position to donate, we would be so grateful if you chose to support us. And as always, thanks for reading.

A food system that values and respects our diversity, cultures, and traditional knowledge is possible. This video by La Vía Campesina explains what Food Sovereignty is; “It places [people] at the heart of food systems, instead of powerful corporations, by building on the principles of solidarity, collectivity and social justice.” You can also watch it in Spanish and French.

The Last Seed is a documentary that features the struggles and triumphs of African small-scale farmers as they navigate the growing threats of the corporate capture of African agriculture. The film also sheds light on the perilous state of our food systems and the urgent need for change. Watch the trailer here.

The first clip of 'The Seed Struggle in Africa', shatters scarcity narratives pushed by industrial agriculture and amplifies the silent war being waged over African seeds. It is a call to action, a plea for awareness, and a testament to the power of truth.

Every resource produced by A Growing Culture, whether a newsletter, article, post, or design, results from countless hours of research, reflection, and the synthesis of profound conversations held both within our team and with our partners and comrades. Behind the scenes, a wealth of effort goes into making these conversations happen, from overseeing our day-to-day operations, securing our funding, to forging deep relationships with communities around the world who are leading food systems transformation. These relationships fuel our thoughts, inform our words, and inspire our actions.

We recognise that no single person can take credit for the work we collectively produce, which is why we prefer to sign as an organisation rather than as individuals. We believe that no idea is inherently our own and welcome anyone who sees value in our work to translate it, build upon it, adapt it to their own contexts, or share it however they see fit.

For this newsletter, we would like to extend our gratitude to Ayesha John, for her support with the data visualisation.

This is a great analysis of what’s going on and it’s great that you have put all the pieces together in an easily understood manner. Thank you.

I hope you can get more donations because the work you do is really critical to understanding the crises we’re in.

I dream of a different world. Not controlled by shareholders and corporations and where greed is shunned and shamed as it has been in most indigenous cultures for generations upon generations.

Loved the piece. Lucid and thought-provoking.